You know “projects” – Rooms that need remodeling. Machines that need repairing. Curriculum mapping or the backward design of your next great unit. Projects are authentic, in-demand experiences. They can be simple and resolved relatively quickly. Or, they can be complex, multi-phased, multi-year, and anything in between–painting a bathroom vs. remodeling a bathroom vs. building a second bathroom in the basement. Appreciating that project work is about the process toward a solution and not just the end product is tough for kids to embrace, and sometimes even their teachers, but it is where critical thinking and learning flourish. It’s messy, circuitous, and herky-jerky, but it builds grit and agency. It’s relevant. It’s rigorous. It’s real.

Through fourteen years of working alongside students as they navigated the project process, I learned three principles I could apply that gave students the confidence they needed to create solutions to authentic problems and pathways to relevant, new learning.

1. Learn to be comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Completing a project is mixed with challenges, creativity, frustration, accomplishment, and success. The teacher cannot control the learning or the divergences it may take during the course of one project, which means teachers should learn to be comfortable with the uncomfortable: They can not be experts in the myriad of project ideas their students will choose, and their students will not be experts in the endurance it takes to move through the process. Instead, teachers and students will be learners together. This not only builds a culture of shared leadership and voice but also one that models good practice when approaching the ambiguous and unknown.

A wise PBL teacher-coach taught me that it takes nine weeks to nine months for a student or teacher to learn effective PBL and build the stamina to delay the gratification inherent with an end product. Regardless of where a project lands on the continuum of PBL–teacher-led to student-led, mini to massive–teachers can coach their students through the process by becoming masters themselves of design thinking and artful inquiry-based questioning with a healthy dose of vulnerability.

2. Create a template of scaffolding and accountability.

While project-based learning is diverse and creative, it isn’t always intuitive for students. Traditional sit-and-git schooling rarely nurtures learning through design-thinking challenges. Instead, it is often rote and micro-scaffolded to appear linear when it actually seems fractured to the learner. In PBL, inquiry sparks curiosity and creativity to “see” problems and then to design projects with strong driving questions that respond to those problems. As students’ experiences in PBL increase, their driving questions become more in depth, take longer to investigate, and share multiple solutions or no clear solutions at all. Throughout the evolution of the project, teacher-coaches model their own curiosity and use Socratic questioning to mitigate students’ frustration with the challenges of self-discovery.

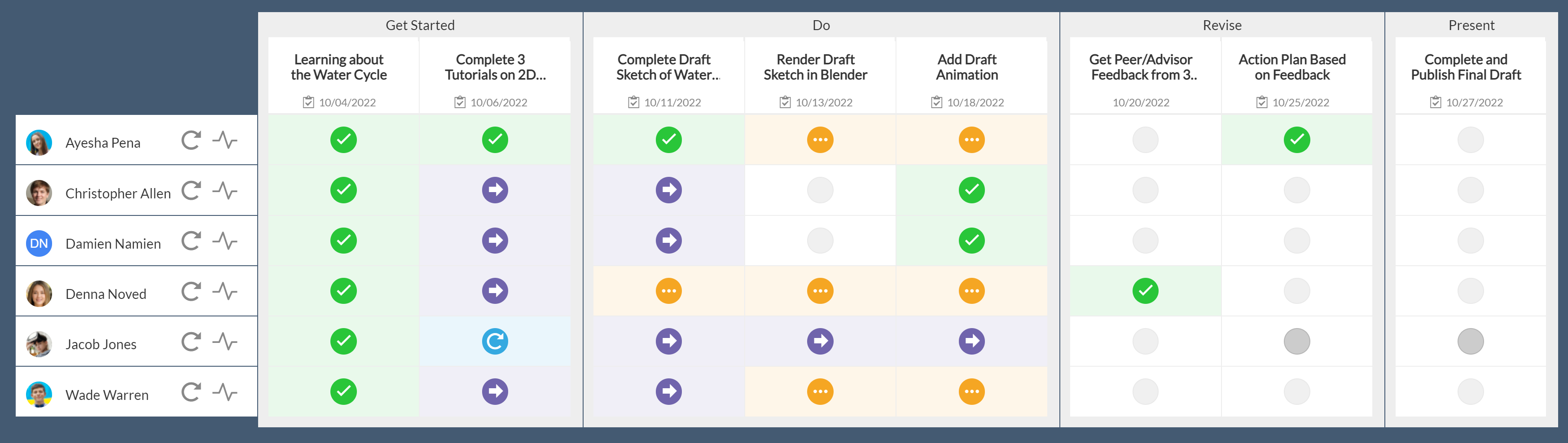

As students build these independent skills, they still need checkpoints. To coach students to tolerate the curves, starts, stops, and multiple steps, teachers should consider scaffolding aids that organize tasks in the common sequence of design or problem-solution thinking. For example, a project checklist should delineate the tasks within the phases of effective project design–proposal, research, planning, production, pre-presentation, and assessment–to serve as a graphic organizer or task board. A project checklist that further divides the phases into weeks will improve project completion, task management and timeliness, and increase student accountability. While the checklist or task board steers students through the work carried out during a project, it supports students’ ability to work independently and with confidence because they know the expectations.

A scaffolded project checklist creates frequent, regular artifact submissions as evidence of student learning, progress, and growth. Lack of artifacts that demonstrate competency of learning targets impedes student and teacher assessments and is the sticking point for critics of PBL. The checklist becomes the center of teacher-student check-ins, and these formative assessments support an environment of personal learning, flexibility, negotiation, adaptability, and perseverance. Besides project checklists and driving-question development documents, Headrush templates and artifact-collection tools create a portfolio of student work. In the end, time and attention to the daily, consistent tasks associated with successful PBL makes the messy project process manageable for teacher-coach and student.

3. Be relevant. Be rigorous. Be real.

Not all projects are envisioned by individual learners nor is the discovery done in isolation of other learners. Some projects will be created by pairs or teams of learners; however, one aspect remains the same regardless of the learner groups or who initiated the learning. Authentic project topics that impact the community produce student engagement. Teacher-coaches should ask students questions like “Who could benefit from this new knowledge? Or, how will you share what you’ve learned?” Or, “How will this solve a community problem or work toward a solution to one?” Linking students to community partners as primary sources immerses students in real problem-solution thinking with real teams of people. This sort of high-level thinking and collaboration with relevant consequences or contributions challenges students to think and learn in new ways and entices them to do the heavy lifting of academics.

While a project could be an individual learner’s plan to complete a social studies standard related to World War II, or a team of students asking, “How can we improve the forest habitat at our school forest to increase the ruffed grouse population,” or any inquiry-based question in between, teachers serve as guides and co-learners and create school cultures where learning engages students in meaningful work.

About Paula Zwicke

Paula Zwicke lives in the Lake Superior region of northern Wisconsin where she led a project-based learning (PBL) high school from an outdoor classroom in the school forest. Her experience – half traditional, half PBL – expands traditional and alternative instructional practices. She works to design schools that engage learners, reduce achievement gaps, inspire educators, and create community partnerships. She holds a BS in English/Secondary Education from Northland College, an MA in Education with an emphasis in K-12 critical thinking and writing program development, and an MFA in Writing. Her stories and essays have appeared in Teacher Powered Schools, The Ruffed Grouse Society magazine, Wisconsin Outdoor News, Wisconsin English Journal, and elsewhere.